x86 101

A crash course on x86 to make it less scary.

So, you want to learn x86? Well, you've come to the right place!

PS: Please excuse the poor drawings. I did my best only having a trackpad for drawing.

Table of Contents

This is by no means an exhaustive guide for all there is to know for x86, but hopefully it will be a comprehensive overview of the most important parts of the language.

- Why?: My reason for writing this in the first place.

- What?: Honestly, what is this?

- Program Components: What are the parts of a typical program?

- Instructions: The types of instructions that exist.

- Math: Mathematical operations that can be performed.

- Stack Based Operations: Operations that perform push/pop on the stack.

- Load Effective Address: Loading the value at a given memory address.

- Compare: Comparison operators for conditionals.

- Jump: Jump to other parts of a program given a memory address.

- Call: Calling other functions.

- Leave/Ret: Exit a function call.

- References: References I used.

Why?

You might be wondering why I would subject myself to torture by trying to learn Assembly in the first place since it's "either too hard" or "it's boring as hell". Well, you're right, it's definitely not the most interesting thing in the world. Since I'm taking a course of offensive security, I kinda need to at least understand the basics of it -- mainly to understand program disassembling for CTF.

So far, there aren't too many simple guides on learning x86 online compared to other languages. So hopefully, this will be a quick and easy guide for you to follow to learn the very basics of x86. 😄

What is x86?

Worse than MIPS. Just kidding. x86 is a variant of Assembly that is commonly written for x86-64 processors which are CISC processors (common in most desktop computers today). x86 is more complex than, let's say, MIPS in the sense that it is designed to complete tasks with only a few instructions rather than using more basic instructions [1].

For example, CISC architectures come with a built-in instruction that performs multiplication without breaking it up into a series of smaller instructions. In the RISC approach, multiplication is actually broken up into a series of a few instructions [2].

; CISC approach

; Imagine if dval1 = 0x5 and dval2 = 0x6

mov eax, dval1 ; Move the first value to accumulator

mul dval2 ; Multiply into eaxIn the RISC approach, it is broken up into a series of other steps.

LOAD A, 2

LOAD B, 3

PROD A, B

STORE A, RESProgram Components

Before we get started with the x86 language, first we must understand the main sections of a program written in C. This will be a very brief guide since there is plenty of info online. Note that what I will be talking about is the 32-bit variant of the x86 architecture.

Heap

The heap is a section of unmanaged memory (in Java, there's GC so technically it is managed there) that is allocated by the operating system. The OS uses the sysbrk syscall to allocate memory from the requesting function. Unlike the stack, memory is not invalidated when the function returns which leads to memory leaks. To avoid this, in C you would release memory with free() after a call to malloc() or one of its variants. The eap grows upward towards higher memory addresses.

Stack

This refers to the region of memory that is allocated to the process primarily to implement functions. This is managed in the sense that the variables created remain local to the function it resides and is invalidated once the function exits (when the stack pointer moves up). The values are still there, but they will be overwritten by the contents of the next function call's stack frame. Two x86 registers that deal with this are:

esp(extended stack pointer) - points to the top of the stack wherepushandpopwill decrement and increment the stack pointer respectively.pushadds an element to the top of the stack whilepopremoves the element at the top of the stack.ebp(extended base pointer) - points to the start of the current stack frame, which is the space allocated for a function call. Thecallinstruction pushes the current instruction pointer onto the stack.

Note that the stack grows downward towards lower memory addresses. This is also where global and static variables are declared.

Registers

These are small storage units located directly in the processor for quick access to intermediate values in function calls. It is known as L0 cache and it is located at the highest level in the memory hierarchy.

There are six 32-bit general purpose registers in the x86 architecture [3]:

-

eax(extended accumulator register) - used for storing return values for functions and special register for certain calculations.-

mov eax, 3 ; Set eax to 3 ret ; Return

-

-

ebx(extended base register) - often set to commonly used values to speed up calculations. -

ecx(extended counter register) - used as a function parameter or a loop counter. Generally used with for loops as the counter. -

edx(extended data register) - also used as a function parameter register likeecxand storing short-term variables within a function. -

esi(extended source index register) - register that points to the where the "source" is located in memory. -

edi(extended data index register) - similar toesi, but it points to the destination.

ebp, esp, and eip are all known as reserved registers.

Instructions

Format

There are essentially two schools of thought for instruction format: the AT&T syntax and the Intel syntax.

In short, the difference is that for the AT&T syntax, the source register is on the left side and the destination register is on the right side while it is the opposite for the Intel syntax.

Instructions typically follow 2 forms:

op arg- there is an operation with only one argument specified.op arg1, arg2- there is an operation with two arguments specified, separated by a comma.

As an example with the mov instruction, it copies the value that is stored by the second argument into the first argument.

mov arg1, arg2Although it is called mov, it actually copies instead, meaning that the value stored in arg2 is actually still there. However, there are some caveats with this specific instruction in general discussed in the next section.

Dereferencing

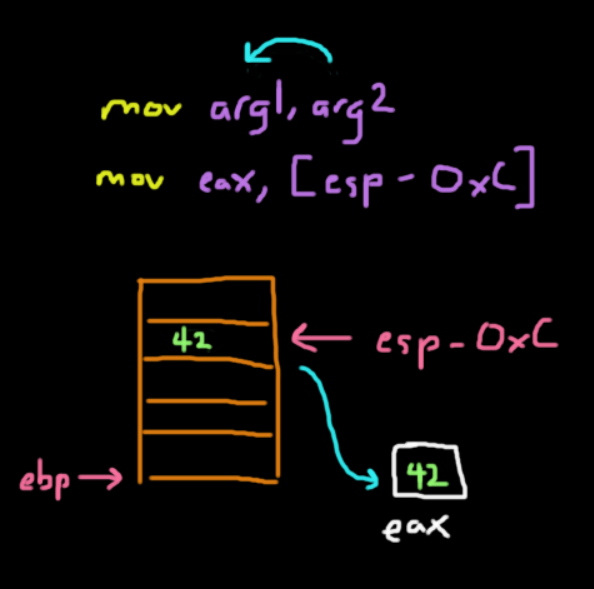

The caveat comes when you are trying to get values from the stack.

When you are trying to get values from the stack, let's say moving a local variable at ebp - 12 (0xC) with a value of 42, you would expect that you would get the value that is stored at that location into eax. This means that eax should have the value of 42 right?

mov eax, ebp-0xCWRONG

ebp - 0xC is an address that refers to where 42 is stored in memory. Simply calling mov will move that address into eax, but not 42. If you know C, you know that we would need to dereference a pointer to get the value at that location. In x86, a similar idea also exists where we can think of using the square bracket notation as a dereference operator.

So to get 42, we would run this:

mov eax, [ebp-0xC]Math

Of course, x86 supports the basic mathematical operators that you would need to perform more complex computations.Addition

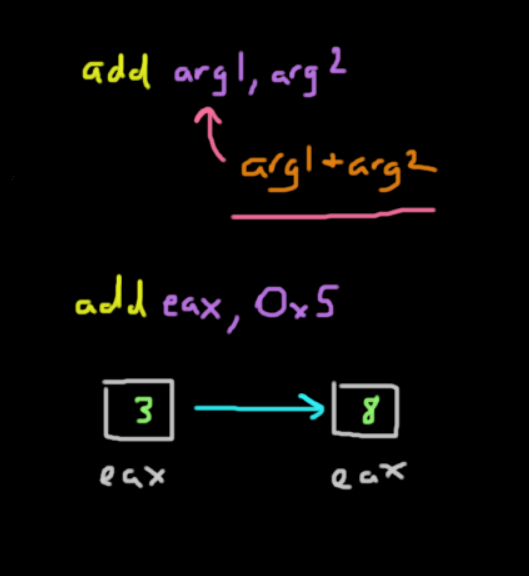

The add instruction is a binary operation that adds two given registers with the format add arg1, arg2 which is the same as arg1 = arg1 + arg2. The first and second arguments are summed and stored in the first argument.

add eax, 0x5The instruction above adds the value in %eax with 5 and stores it back in %eax.

Subtraction

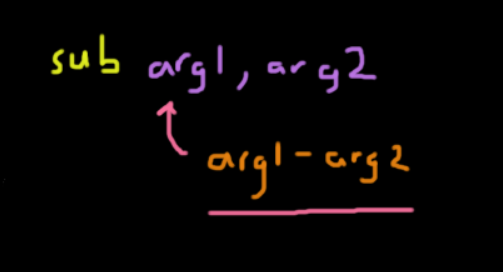

This is a binary operation that subtracts the second argument from the first: sub arg1, arg2 is the same as arg1 = arg1 - arg2.

sub esp, 0x4The instruction above moves the stack pointer down 4 bytes. This can also be done by adding a negative value with a lower overhead.

Multiplication

Multiplication is a bit more complex since it comes with several varying instructions. Also, its destination register varies depending on the memory size of the value you are multiplying with.

*Note: The terminology here is different than with other architectures. A word is 16 bits (size of the register) and a doubleword is 32 bits.*

-

Multiplying 2 bytes

- This is a common case where we move one of the operands into register

%AX. Then, we callmul <arg2>which would perform%AX = %AX * arg2, wherearg2is some register and not an immediate.

- This is a common case where we move one of the operands into register

-

Multiplying 2 words (16 bits)

- This operation performs multiplication with two 16 bit values.

- The multiplicand, or number being multiplied, is stored in the

%AXregister and the multiplier is a word stored in memory or another register. -

The syntax is similar to before, where we call

mul <arg2>which performs%(DX:AX) = %AX & arg2.- The result is actually stored in two registers.

-

Since this allows for much larger results, the product of two words can result in a doubleword, which means it needs two registers to store the entire result.

%DXholds the upper 16 bits of the result while%AXholds the bottom 16 bits.

-

Multiplying 2 doublewords (32 bits)

- The idea is similar here, but we use the extended versions of registers such as

%EAXand%EDX. - This is also called as

mul <arg2>. -

the result of this could be a

qwordor quadword, so we would need to use 2 extended registers to store the result.%(EDX:EAX) = %EAX * arg2.- Both

%EDXand%EAXstore 32 bits. - Like before,

%EDXstores the upper 32 bits and%EAXstores the lower 32 bits.

- The idea is similar here, but we use the extended versions of registers such as

-

Of course there is

imul, which handles signed multiplication.

Division

Like with multiplication, division also has the same rules for dealing with different size divisors

-

Divisor is 1 byte

- First, we place our dividend (number we are dividing into) in

%AX. - The divisor is then another register or memory location we specify that has the divisor, so the operation works like this:

%AX / arg2. - The result will be stored in two registers:

%ALand%AHwhich store the quotient and remainder respectively. - To perform this, call

div <arg2>

- First, we place our dividend (number we are dividing into) in

-

Divisor is 1 word

- Here, the main difference is that the dividend (32 bits) is placed into the

%(DX:AX)registers where the upper 16 bits are in%DXand the lower 16 bits are in%AX. - After dividing, the 16-bit quotient goes into

%AXand the 16-bit remainder goes into%DX

- Here, the main difference is that the dividend (32 bits) is placed into the

-

Divisor is a doubleword

- The dividend here is assumed to be 64 bits stored along the

%(EDX:EAX)registers. - After dividing, the quotient goes into

%EAXand the remainder goes into%EDX.

- The dividend here is assumed to be 64 bits stored along the

Stack Based Operations

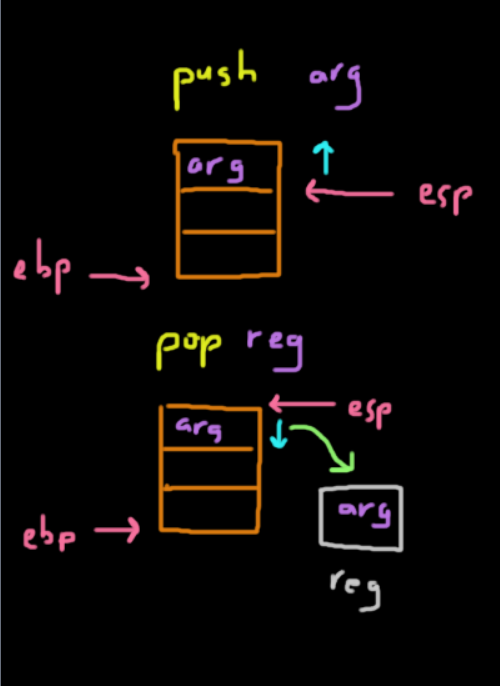

Stack based operators are designed to manipulate registers that correspond with the stack pointer, such as %esp and %ebp.

Keep in mind that the stack pointer grows downward in memory, so the "top" of the stack is really at the bottom.

Push

-

The

pushinstruction is designed to put stuff on the top of the stack.-

How it accomplishes this is by decrementing

%espby 4 bytes (to allocate space for an address on 32 bit systems) and then places the value inside those 4 bytes.push <arg>

-

Pop

-

The

popinstruction is used to pop or remove data from the top of the stack pointed by%esp.- This works by incrementing

%espby 4 bytes (on 32 bit systems) and copies the value to the corresponding register. -

The actual data isn't cleared itself on the stack, but since the stack pointer is above it, the data will be overwritten the next time the stack pointer goes past there.

pop <register>

- This works by incrementing

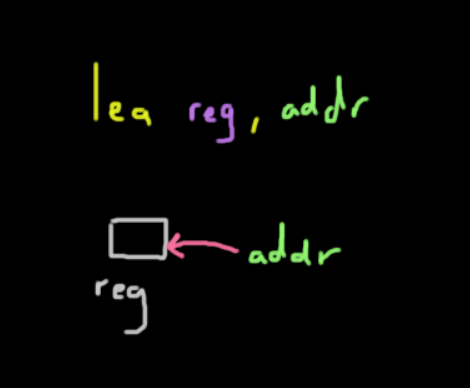

Lea

This instruction stands for load effective address.

It places the address of the corresponding value specified in the second argument and places it into the register specified by the first argument.

The instruction was mainly included to add support to higher level languages like C where it wants the address of some value whether they are arrays or structs. It would be equivalent to the & operator in C.

Let's say we have a struct defined in C like this:

struct Point {

int x;

int y;

int z;

}If we were to access the z coordinate of an array of Points inside some for loop, we would run something like this:

int z = points[i].z;In x86, the equivalent statement would be:

MOV EDX, [EBX + 12 * EAX + 8]- Recall that the

MOVinstruction is used for moving values from the second argument to the first. - The brackets are used as a dereference operator to get the associated value at that address.

- We are assuming that

%EBXcontains the base address of the array and%EAXcontains the counter variable. - Assuming a 4-byte alignment, we multiply the counter

%EAXby12since thePointstruct has a size of12bytes (from 3 32-bit integers). -

The offset to get the

zvariable is8bytes since there are 2 preceding integers,xandy. Now that's great for getting the value we want, but what if we just wanted the actual address in memory. In C, the&operator comes in handy and we can write something like this:int* p = &points[i].z; -

The code above will get the address of the

zvarible in the struct and store that in an int pointerp. Below is the is the compiled version of the code, where we load the address into register%ESI.LEA ESI, [EBX + 12 * EAX + 8]

But Stan, Wait!

Can't we just do the same thing by writing MOV ESI, EBX + 12 * EAX + 8?

Well no, we cannot. The explanation will become clear after reading a riveting discussion on Stackoverflow spanning 2011 - 2018 [4].

To simply put it, here are the main points of why that is not possible:

- The

MOVinstruction is not designed for just calculating the address of a given memory location. Its job is to access whatever value is stored at that address, meaning it actually takes extra time to read the contents of that memory location.LEAjust does the math on the given values. - It is not valid to perform some form of computation without some brackets or parenthesis.

- Assuming that there is a specialized function for

MOVthat did allow for the line of code above, it would make the syntax less clean. It is subjective, but it is much easier to distinguish loading from memory and calculating an address if you have 2 different instructions.

There are probably more reasons, but in general, having a dedicated instruction for calculating addresses is a lot cleaner and more optimized than overloading an existing instruction which increases complexity and decreases readability.

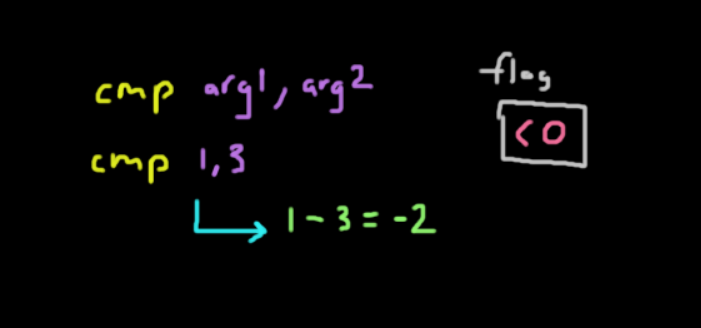

Compare

The cmp instruction is actually the same as the sub instruction except that instead of storing the result in the first argument, it will set a flag in the processor.

The instruction can be executed as cmp arg1, arg2.

That flag will have these possible values:

< 0-arg1 < arg20-arg1 == arg2> 0-arg1 > arg2

The flag being stored is actually the value of arg1 - arg2.

As an example, this is how it would work:

cmp 1, 3- This instruction would perform

1 - 3, setting-2inside the flag which tells us thatarg1 < arg2. - Keep in mind that this is not really a valid way since we cannot compare 2 immediates directly.

- The first argument is usually a register while the second one can either be an immediate or a register.

Now there are many other examples of using the cmp instruction along with many other acceptable arguments, which can all be found here [5].

Jump

Typically when using the cmp instruction above, it is followed by a jmp or jump instruction. This instruction takes in a single argument for the jump address as its parameter.

jmp addrThe jump will be taken based on the value of the flag in the processor. When a jump is taken, the eip register is set to that argument. Of course, there are many variants of the jump instruction that change the flow of the program based on the value of the flag. The jmp instruction shown above is the unconditional jump.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of the different jump instructions that exist. These are mainly the common ones.

je(jump equal) - jumps if equaljz(jump zero) - jump if zerojl(jump less) - jump if lessjg(jump greater) - jump if greater

There are plenty more that can be found here [6].

Below is an example program written in pseudocode on how it may work. Addresses are on the left and instructions are on the right, assume that the eip points to addr3:

addr1 instr1

addr2 cmp 1, 3

addr3 jl addr10

addr4 instr4

... ...

addr10 instr10- Looking at the example above, the jump would be taken to

addr10since1 < 3and we are usingjl, meaning jump if the first argument is less than the second. - If we used

jg, theeipwould move toaddr4.

Now you may have noticed that I used the word flag a lot in the last two sections, but what the heck is it?

The idea of the FLAGS register is to serve as a status register that contains the current state of the processor. This essentially means that this 16 bit wide register holds a lot of information as to what is going on in the processor.

If the entire state of the CPU is stored in a single register, how do we keep track of multiple independent states?

The idea of using a single register is to save space. Luckily through bitmasking, we can specify a specific set of bit(s) to represent the state of a certain piece of information. In short, each flag or state information is mapped to a specific set of bits. Confusing right?

For example, let's say if we are performing some addition and a carry value has been generated by the ALU, the carry flag or CF is set to 1 to let us know that this has happened. This 1 is just 1 of the bits in the 16-bit register representing the state. To get the value of CF specifically, we use a mask value of 0x0001, meaning that the least significant bit corresponds to the carry flag.

The most common flags that are seen are typically CF, ZF, OF, PF and SF. Since this is only a brief overview, you can see a much more detailed breakdown of the x86 flags here [7].

FLAGS register is not limited to just 16 bits, as some processors have 32-bit and 64-bit register sizes. The 32-bit variant is denoted as EFLAGS while the 64-bit variant is denoted as RFLAGS.

Call

Perhaps this is the most important instruction of them all. It is a simple instruction on the surface that takes in a single argument.call <func_addr>This is designed to "call" a function in a program or library. When you disassemble your C program, you will notice that calls made to standard C library functions like printf all point to some memory address.

The way that call works is that it pushes the return address, or the current value of eip, onto the stack and jumps to the argument.

In other words, this means that call <func_addr> is equivalent to:

push eip

jmp funcWhat this does is create the stack frame which in essence places all the parameters, the return address, and the function itself in the right order on the stack so it can execute and return to the caller. Every single function that is called will have its own stack frame, where the base pointer ebp contains the start of the stack frame and the esp points to the top of the stack frame.

To call a function with parameters, it would look something like this. This is what foo(a, b, c) would look like in x86:

push c

push b

push a

call fooNote that we always push in reverse order since a stack is LIFO. Recall that all the parameters are stored on the stack. To access them, we can write something like this:

pop eax, [esp + 0] ; Return address

pop eax, [esp + 4] ; Parameter 'a'

pop eax, [esp + 8] ; Paramater 'b'

pop eax, [esp + 12] ; Parameter 'c'Realistically, we are missing the stack base-pointer register, which helps us keep track of where the start of the stack frame is located since handling functions without it can be quite messy.

pop eax, [ebp + 16] ; Parameter 'c'

pop eax, [ebp + 12] ; Parameter 'b'

pop eax, [ebp + 8] ; Parameter 'a'

pop eax, [ebp + 4] ; Return address

pop eax, [ebp + 0] ; Saved stack base-pointer registerLeave/Ret

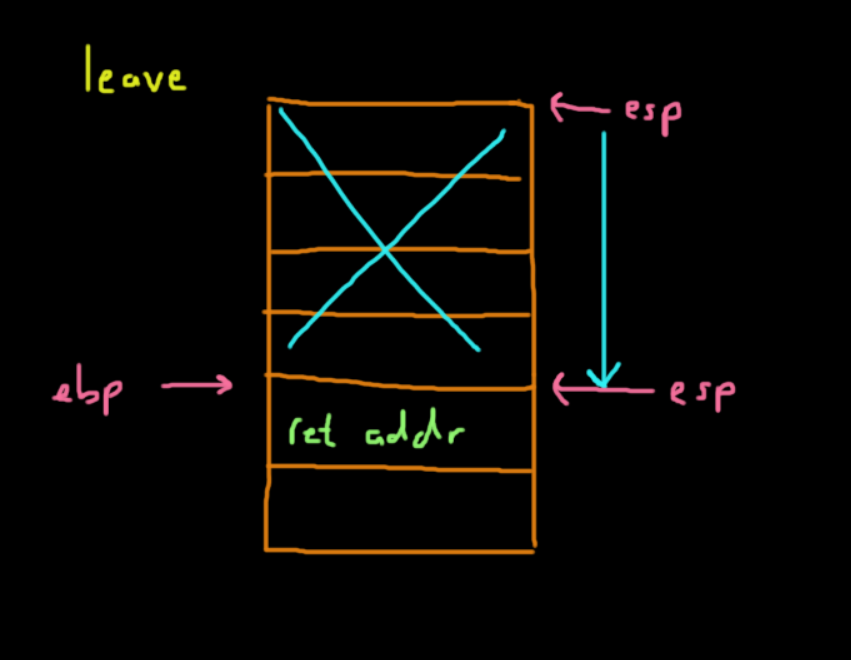

These two instructions are always used at the end of a given function. The leave instruction is always followed by the return instruction as seen in disassembling C programs.

These two instructions make up what we know as today as a single return statement in higher level languages like Java or C. They must be used together as they clean up the stack frame and returns to the correct part of the program.

leave

retThe leave instruction performs the clean up of the stack frame. It:

- Shifts

espto whereebpis located, which is the base of the stack frame for the current function (callee). - Pops from the top of the stack into

ebp, which holds the address of the old stack frame (caller).

In x86, it is leave is equivalent to this:

movl ebp, esp

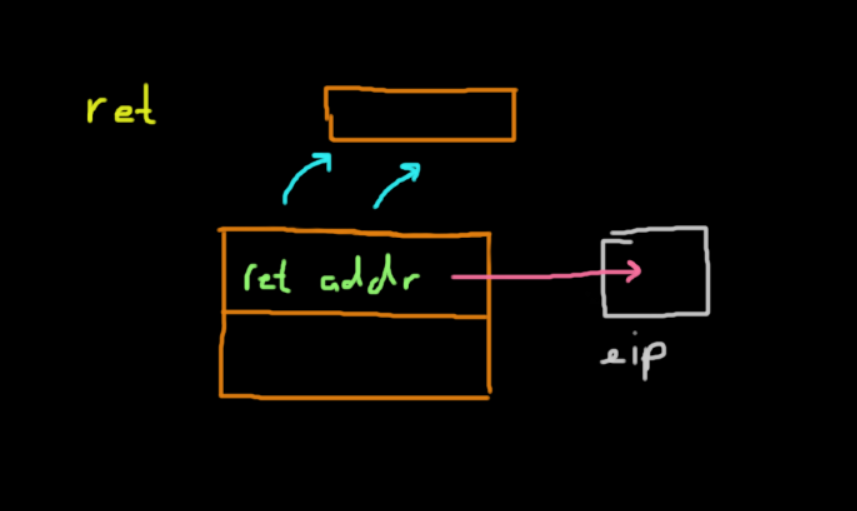

popl ebpThe return instruction takes the value at the top of the stack after leave is called, which is the return address to the caller, and pops it into esp. In the end, the program continues executing where it left off in the caller function.

It's time for me to leave and ret

Understanding x86 is crucial in understanding and developing future exploits of your own. I really hope this helped to make x86 seem a little less scary.

There is, of course, a lot more to learn, but this should lay the groundwork for future research. Have fun!